Author: Robert Franken

I believe that we’re focussing way too much on women.

Unpopular opinion?

It might sound a bit provocative, so let me explain.

For a significant time now, our focus has been on promoting women into leadership positions and on overcoming gender gaps in our companies and in our societies.

And although those are the right things to do, we are missing something important here. We haven’t answered a simple question: Who is responsible for our status quo? Who has set the rules for our actions? What is the norm for our behavior?

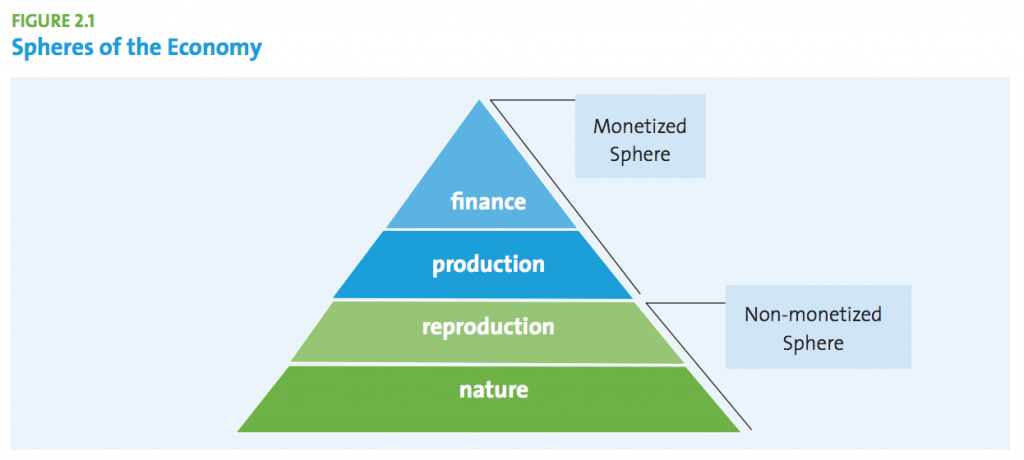

The underlying framework of such a status quo is a system; a system in which we all try to perform, to accomplish, to survive, to be successful, to make a career. There are quite a few names for this system, but I prefer calling it “patriarchy”. But if you’d just like to call it “a system” – no problem at all!

Men are and have been the focal point of this system and men profit from this system, no matter if they are supporters of patriarchy or just beneficiaries of the system’s outcomes and opportunities.

If you are born a man, you can’t help but being rewarded by the system of patriarchy. It has been designed for the likes of us, for the likes of me, since I do identify as a cis gender heterosexual older white male.

Women can also profit from a patriarchal system, depending on their degree of adaptation to the system. And like we all do, women have to adapt to the system in order to be able to work and to live within it. Or simply in order to function in this system, to cope with it, to get along.

But adapting to the system is taking its toll. Since the system is designed mostly for men (and by men), the task of adaptation is a much bigger one. And it is a task that requires energy, dedication and sacrifice. Dealing with an almost unbearably huge mental load is one of the most drastic systemic outcomes for women.

As human beings, we are reacting to a systemic framework in comparatively smart ways. Our behavior adapts to what the system signals to us what would be a smart behavior. A behavior, which would be welcomed and rewarded by the systemic norms. Systems reward smart behaviors according to the system’s rules.

So back to my initial remark, that we are focussing too much on women.

We have also quite recently, I believe, embarked on a journey to empower women. And I don’t think we should do that, either! And yes, I will try to explain this, too.

Women are empowered. They have been empowering themselves for ages. Because they had to. Living in systems which don’t fulfill your particular needs in the first place needs a lot of empowerment and even more self-empowerment.

Women are not broken, the system is broken. And the system is upheld by patriarchal parameters. But instead of fixing the system, we are fixing women. To make them fit into the system. At this point, I sincerely hope that this sounds as absurd to you as it does to me.

Keeping in mind what I said about systemic preconditions, we should stop fixing women and instead fix the system. And since the system has been designed for and is upheld by mostly men, I think men should be the primary focus of systemic change towards a more gender equal society.

And thus, we need to empower men.

This may sound odd, if not reactionary. Empowering men? In a system, which already provides huge boosts for male egos? Where men are the norm and marginalized social groups are struggling?

Yes. I believe it is necessary. Not despite these systemic outcomes, but precisely because of them. I believe that men are the key to changing our systems and to create a path towards gender equal and fair and inclusive organizations and societies.

Men are struggling. Masculinity can be a very fragile thing. Men live under the fear of losing privilege and power. They very often believe that they need women to deliver stability and care. Some men only function because there are women in their lives who provide them with an emotional foundation.

And deep within, most men are aware of their emotional dependency on women. But they can’t admit it. Instead, they lash out, attack, blame and behave in a way which can only be described as a display of toxic masculinity.

Don’t get me wrong, please: The men I am writing about aren’t toxic, the underlying concepts of masculinity are. And thus, we need an evolution of male socialization and of male behavior.

In an organizational context, we need to show men where their true power lies. Not within homosocially reproducing monocultures, but in self-empowerment. Not within exclusive in-groups but in diverse and inclusive cultures and networks.

Men do have a choice, but it’s a demanding one: Either, they become a part of the solution, or they are automatically a part of the problem.

But before some men revolt or take to the barricades: I don’t blame individual men, when I am advocating for change. What I do is I am addressing a systemic malfunction. Men have to adapt to systems, too. And they have been compromised by the systems, often without knowing.

I would like men to embark on a learning journey about themselves and their roles. And about the systems they live and work in.

To me, the key to change is a process of reflection of men. We need to become aware of our privilege, especially if we don’t feel it. If we feel accused and neglected and blamed by all those attempts to heal a sexist, misogynist, exclusive, classist monocultural system, then we have a lot of work to do.

We are key players in the process. We need to become allies in changing the system. We need to live up to our responsibilities and play a role as change agents. We need to identify how and where our behavior is harming people who are different from us.

“People who are different from us” is quite an accurate definition of the concept of diversity, which goes way beyond the binary and narrow debate of male vs. female. We’re all so much more than just men and women.

We need to understand people’s access to our systems. How does the world look like for a person who is non-white, trans, homosexual, poor, disabled, illiterate, introvert or else? How does our world feel for others?

Our approach to understanding these facts must be an empathic one, not just a rational one. We need to educate ourselves and learn about our biases and about concepts such as intersectionality.

Diversity is very demanding, very exhausting. But we must all go to work and create inclusive and fair systems that are based on equality. Our KPIs shouldn’t be awards or manifestos or metrics from the pipeline only – but a feeling of belonging of those who haven’t yet had equal access.