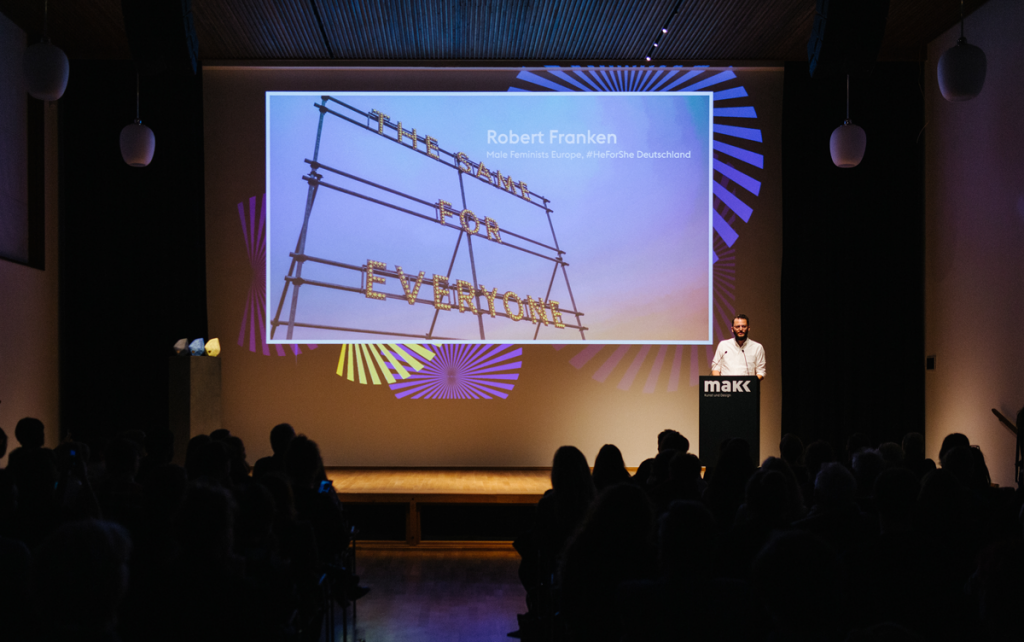

On November 8, 2018, I had the opportunity as well as the honour to hold the keynote speech at this year’s #iphiGENIA Award ceremony at the Museum für angewandte Kunst MAKK in Cologne, Germany. The full speech has been published at IGDN’s website (verbatim). This is a an edited and abridged version of the keynote, in which I talked about (male) privilege, awareness, solidarity, feminist impact and changing norms.

(Photo by Florian Yeh)

My name is Robert Franken. I became an activist for gender equality and diversity, more or less. And, admittedly, I became an activist of privilege.

My privilege is a privilege that I share with quite a few people, I believe: I’m a 45 year old, white, heterosexual, tall, cis-gender male who is living in Germany (in case you don’t know what the term „cis-gender“ means: cis-gender is a term for people whose gender identity matches the sex that they were assigned at birth. The opposite, of course, would be transgender.)

And here’s a piece of advice for all the guys: You are not suposed to be ashamed of your privilege – but you need to be aware of it!

Again: white, heterosexual, tall, cis-gender, German – You can’t be much more privileged than I am in this world, even if you tried very, very hard.

And my privilege of truly global scale is the number one reason why it took me so long to realize that there are quite a few things going terribly wrong in this privileged world of mine. Not for me, though, but for a lot of other people.

Have you ever thought about your privilege? Have you ever made up your mind about how your privilege constitutes your status? If you are privileged, of course.

It can be a pretty sobering experience. I mean, it sounds good: „I am privileged.“ But when you think about it: It becomes very normal very soon. It’s just your personal reality. Your routine. Your norm.

You’re getting used to it, and when you’re getting used to something you’re losing awareness of the very fact that it has always been there: your privilege. It may not feel like being fun anymore, maybe it never has. It’s just normal.

There’s this diversity awareness exercise you might have heard of or even experienced yourself. Imagine a group of people forming a line, holding hands. They’re being asked questions. Questions such as „Do you think your gender is properly represented in the media?“ or „Did you have access to a full school education?“. If the answer to one question is „Yes“, then the participants are being asked to take a step forward.

You can also add questions where a „no“ as an answer would mean a step back. And you can use very tough and challenging questions. For instance: “Have you ever been a victim of sexual harassment?“.

The goal of this exercise is, of course, to challenge privilege and to create awareness for discrimination; to prove that the particular group is much more heterogenous than you would think in the first place, and, that privilege sometimes leads to discrimination – and vice versa.

So eventually, when the exercise is over, you would ask the people standing in the back how they’re feeling. And they wouldn’t feel that great, actually. And that’s because they, once again, are being confronted with their personal discriminatory past and/or present. They’re probably quite used to that, but nevertheless, this exercise sometimes works as a kind of trigger.

The most interesting part of this exercise, however, is how the people in the front are feeling. The people who would be answering „Yes“ to almost every single question. They are the privileged ones, that’s quite obvious, isn’t it? But, awkwardly enough, it doesn’t seem to feel particularly good.

In fact, the people who are standing in the front feel extremely weird. „Weird“ as in „uneasy“ as in „bad“! And that’s because they have just been confronted with their privilege. Maybe for the very first time ever in their whole life!

So, what have they been missing?

Well. There’s so much discrimination in the world of ours that it would take ages to even come close to a summary. I feel that it’s quite an obligation to confront ourselves with at least some facts that are driving inequalities. With the dark side, if you like.

We need to acknowledge a sad fact: Germany is not doing very well in some areas of gender equality. And I will spare you the discussion around the almost untranslatable phenomenon of the „Ehegattensplitting“. Only so much: We’re the only country in the world which is rewarding a husband for a stay-at-home wife… sorry: a stay-at-home partner!

There are even worse imbalances. You’ve surely heard of the vicious circle of gaps: a gender care gap leading to a gender pay gap leading to a gender lifetime earnings gap resulting in a massive gender pension gap aka „Altersarmut”. These are embarrassing facts for one of the wealthiest economies in the world.

I am particularly interested in the gender care gap. Why? Because it is one of the main reasons for all the other economic inequalities between the genders.

According to the latest inequality report („Gleichstellungsbericht“), the average gender care gap in Germany is 52.4 percent. What does that mean? This means that, on average, women are doing 87 minutes more care work per day than men. Every day. The most dramatic care gap occurs at the age of 34: Women of that age are doing more than five hours of care work every day – men only two and a half hours. This represents a care gap of more than 100 %!

And why at the age of 34? Well, this is when there are children in the household. It’s as simple as that. With our family structures and our strange out-of-date attribution to motherhood, women are still a kind of a default option when in comes down to childcare.

This has to change if we really want to tackle the gender pay gap and all the other financial imbalances that follow and that have dramatic consequences.

I you are a woman, sooner or later, you might find yourself in the trap sociologists have called „retraditionalisation“: modern couples are entering the delivery room at the hospital – and out come couples who act like it’s 1958. It is a trap for women, because they are still the „default option“ when it comes down to childcare.

And finally, a short glance on our economic paradigms: If you look at the DAX 30 companies, you’ll have another sobering moment. 92 % of the board members are male. Germany is the only country in the world which hasn’t got a single female CEO in one of its top 30 listed companies. It’s more likely for a man named Thomas to become a board member than for a woman. We’re talking about monocultures here.

If you google for the term „Vorstand“ and switch to image search, the search results are close to satire. A smart mind once coined the term „homosocial reproduction“ which basically means that people are hiring people who are resembling themselves rather than diving into diversity. It’s a diversity horror movie with a lot of sequels. There’s not much more progress in politics, either: More men with the beautiful German name Hans have become state secretary than women.

Let’s face it: Women will not be able to initiate a turnaround here by themselves. And they shouldn’t have to!!

The obstacles that come with working in a sexist culture are beyond any individual’s control. Or, as writer and laywer Ephrat Livni has argued in a recent article for Quartz.com:

“It’s the society we operate in that needs fixing, not how we ask for money, the tone of our voices, or our outfits.“

We need to stop fixing women. And we need to include the other 50 % in order to make change happen. In order to find a collective answer to the question: How do we want to live and work together in the future? In order to achieve this, we, as men, need to live up to our responsibilities!

But, as you all might have experienced yourselves, there’s quite a massive backlash to gender issues at the moment. It’s a global backlash. It hasn’t started with Trump, but the unbearable misogyny, white supremacy, racism and sexism of the Trump era shows that a lot of men – and some women, too – have decided to remain a part of the problem rather than joining forces and become a part of the solution. As a matter of fact, sexism and misogyny are on the rise.

A sexual predator is president of the United States of America and a sexual offender will be in the Supreme Court until his death. The Hungarian prime minister has banned Gender Studies from the universities because he thinks that they are, “a threat to the traditional family“. An Austrian female politician has been sentenced for calling out a male harasser, because the judge doubted her evidence. The terrible stories keep on coming, day by day.

And gender seems to have become (or maybe alway has been) a battleground. Many people – predominantly men, but also women – feel offended by the mere discussion of gender-related issues, let alone by a debate on gender equality. The concept of masculinity (and of femininity sometimes) seems fragile. Or at least, I’ve been trying to explain some of the more severe attacks on feminism and feminists by fragile masculinity.

Am I wrong? Maybe.

But the concept of gender is so very personal and gets so uncomfortably close to our socialization as humans, that the only way to maintain our foundation as human beings very often is to lash about and hit all those who question this foundation. And those who want do debate gender roles and responsibilities.

As I said: The backlashes are everywhere, and they seem to be getting worse. Is it just patriarchy’s final battle? Or is that, what we call „patriarchy’s dividend“, so attractive, that a majority of people is once and for all working on upholding its systemic paradigms?

To me, one thing is cristal-clear: men have to get moving. We have to stand up and show sustainable solidarity. Solidarity in the fight to end patriarchy. This fight would be for our own good. The sooner we realize this, the better for us all.

Victoria Bissell Brown, a retired history professor at Grinnell College in the U.S. has written an article for the Washington Post in which she’s calling on all men. She writes:

„In the centuries of feminist movements that have washed up and away, good men have not once organized their own mass movement to change themselves and their sons or to attack the mean-spirited, teasing, punching thing that passes for male culture. Not once. Bastards. Don’t listen to me. Listen to each other. Talk to each other. Earn your power for once.”

So again: Gender equality is a responsibility for all men. Yet, men seem to have a problem with their responsibility. We still haven’t organized ourselves around the task of creating a gender equal society or to ensure fair and inclusive systems of mutual support. We still don’t engage at scale.

Let me give you just one example: Women in Iceland went on general strike because they feel discriminated against by a gender pay gap of 13 percent. The pay gap in Germany is 21 percent. No strike. Not by men, not by women. I am asking you: Where’s our consternation, where’s our rage and where’s our solidarity for this fundamental issue? We all have our answers. And maybe we have to turn those answers into collective action.

If I had something to say, I would make the diversity awareness exercise I have been talking about a few minutes ago a monthly routine. Maybe with a changing set of questions. Why? Because it is so utterly important to challenge our norms and biases on a regular basis. By doing so, we would be training ourselves to change our perspectives. To learn to walk in other people’s shoes. To create an understanding of systems and norms and privilege and discrimination. To develop an empathic approach to diversity & inclusion.

Before I end, I’d like to sort out one or two things, so we all wouldn’t be confusing them any more. I want to do this by quoting Canadian author Justine Musk who is commenting on basic truths:

“The enemy of feminism isn’t men. It’s patriarchy, and patriarchy is not men. It is a system, and women can support the system of patriarchy just as men can support the fight for gender equality.“

Well, good luck for all of us!