„The enemy of feminism isn’t men. It’s patriarchy, and patriarchy is not men. It is a system, and women can support the system of patriarchy just as men can support the fight for gender equality.“ (Justine Musk)

Most people are done with patriarchy. No, really. I mean it. They have analyzed and studied it. They have experienced its narrow limitations and its discriminatory nature. They came to the conclusion, that patriarchal systems are counterintuitive in times, where we’d rather embrace diversity than stick to predominantly male monocultures. We need a multitude of perspectives in order to cope with what we have framed in a cryptic acronym: „VUCA“. Volatility, uncertainty, complexity, ambiguity.

And yet, we haven’t abolished patriarchy once and for all. We still rely on it in times of radical change. This is absurd. We almost behave like alcoholics, well aware of the fatal implications of the drug.

But why?

Female authority as a key concept

Antje Schrupp, a German political scientist, feminist and author, wrote an excellent piece on female authority back in 2001, in which she describes how the patriarchal system remains in charge simply because a trusted new approach is yet to be established. Patriarchy’s logic, Schrupp explains, has left women with only two alternatives: They can either adapt to roles and behaviors typically framed as female, or, they can strive to become like men themselves. And, of course, this is a choice between the devil and the deep blue sea.

Sometimes, while trying to fully grasp the implications of patriarchal systems, I get the impression that there’s a fight going on on all sides: a fight for the interpretation sovereignty about what is to become an alternative system to patriarchy. And only after having read Antje Schrupp’s essay, I have understood that we are still lacking such a new order. The disorder, Schrupp has already been pointing at some twenty years ago, is still affecting large parts of our systems today.

This disorder leads to an increasing alienation: Women (and more and more men) feel like they don’t belong any more. Whether it is political parties, transnational organizations or companies: All of these institutions find it harder and harder to create attraction and, even harder, retention. And I have an inkling, that this may well have to do with the rules, by which they are still playing out campaigns or employer branding.

New rules, new narratives

The old narratives won’t resonate any longer. But what’s next then? Is this just a challenge for a new kind of storytelling? I believe, that it’s a discussion much more fundamental. It’s about a completely new set of rules.

There are still no widely accepted rules for social cooperation in a post-patriarchal society. And a lot of people (women* and men*) remain „within the logic of the patriarchy by constantly protesting against its rules or by interpreting their feeling of alienation by claiming that the patriarchy has indeed not ended yet.“

We are still struggling, both with the alienation by existing systems and with our inability to live and act by a fundamentally new set of rules. This might also explain, for example, why some men are fighting organizational promotion of women as being discriminatory against their own career advancements.

Men being stuck in traditional dramas

Instead of focusing on their impact while changing the existing system, these men are acting within the old paradigms of a system they almost certainly despise for its discriminatory setup. They simply can’t see any other way, they’re stuck in a mono perspective: get a job, make a career, establish a status and thus become attractive for a partner–then (and only then) you can have a family and a meaningful life.

It’s pretty obvious that this way of defining meaning in life has several inherent dangers. If you pursue such a one-way street in life, you’ll lack resilience every time something goes wrong. You’re only option will be to push through. The outcome can be devastating, when relationships, finances and health are at risk.

Our individual and collective actions are once again lagging behind our ways of thinking, which are already crossing boundaries from time to time. We have adopted new ways of thinking our societies, economies, businesses etc., but our actions still support the very foundations of the systems in charge, above all: the patriarchy.

Caring economy as an alternative framework

In order to overcome this paradox, we must change our reference point. No longer should we make the existing system the foundation of all our endeavors and ambitions, but a new system of sustainable relationships, where humans are no longer a disposable factor within certain economic cycles, but at the center of a caring economy. This may sound comparatively socialistic when we first hear it, but, in fact, it is most certainly the only way of creating a future foundation of social welfare economies.

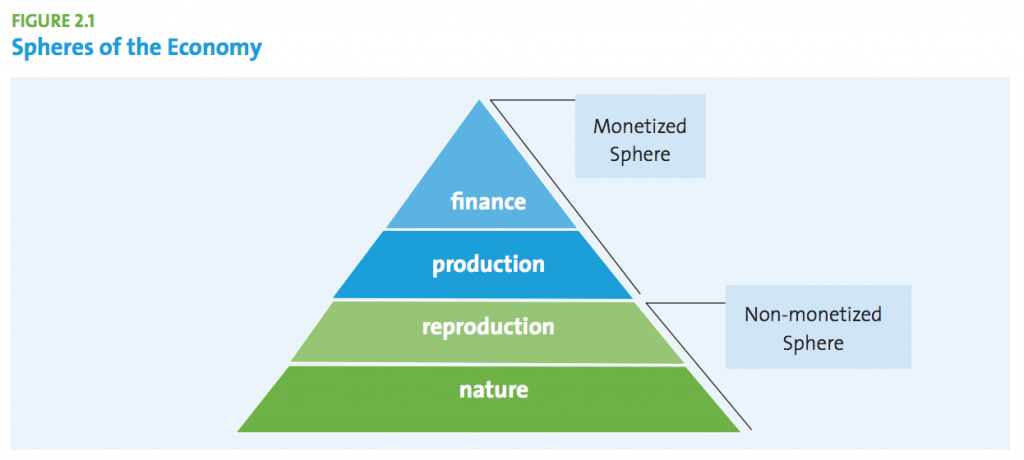

If we take a look at the spheres of the economy it becomes obvious, that there are two spheres which represent a monetized economy (finance and production), while the remaining two spheres (reproduction and nature) are part of a non-monetized (or: maintenance) economy. We are looking at nothing less than at the core of capitalism’s drama. The barrier between production and reproduction marks the single point of failure of our economic system: It is a system of exploitation. And a one-way street.

By breaking up the barriers between the two spheres which are so deeply interlinked and dependent on each other, we could initiate a holistic approach to answering fundamental questions: How do we want to live and work together in a future where paid work will become an increasingly volatile factor while care work will even more become the centerpiece of functioning societies?

„Female“ symbolic order

Women are the cornerstone of such a caring economy. In a talk from 2017, author, philosopher and learning therapist Dorothee Markert relates to the Italian feminist thinkers, who recommend substituting female power relationships by authority relationships. Markert, once again, points to Antje Schrupp, who argues in her publication „ABC des guten Lebens“ for these new kinds of relationships among women, which could create a new foundation of social cooperation and unleash „independency from a male-shaped symbolic order“.

The key question for me would be: How can I create impact and how can I support the development and establishing of a „female*“ symbolic order? I have no answers yet, only ideas. But I am curious and thus looking forward to seeing the debate unfold.

Author: Robert Franken

I’m heading home from, let’s say, from a night out with friends, strolling through a quiet part of town, and I’m walking behind a woman. She’s a bit slower than I am and I’m slowly catching up. And all of a sudden, I realize how uncomfortable she might be feeling. So I’m beginning to walk a bit slower, adding some distance between me and her. But yet again, since this is a deliberate decision, I’m getting the feeling of being somehow manipulative. It’s a dilemma.

I’m heading home from, let’s say, from a night out with friends, strolling through a quiet part of town, and I’m walking behind a woman. She’s a bit slower than I am and I’m slowly catching up. And all of a sudden, I realize how uncomfortable she might be feeling. So I’m beginning to walk a bit slower, adding some distance between me and her. But yet again, since this is a deliberate decision, I’m getting the feeling of being somehow manipulative. It’s a dilemma.